The US aggression on Venezuela and the forcible capture of President Maduro raise a serious question about the efficiency of the UN as a global watchdog. It’s time to examine whether nations, which designed the post-1945 system, still regard themselves as committed to it, or treat the UN anchored treaty-based project as optional.

Rahul Pawa

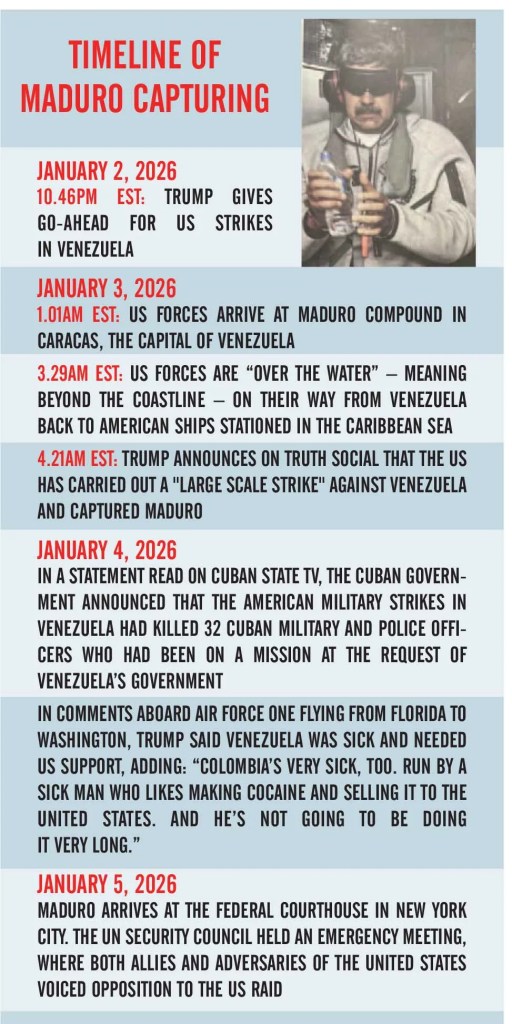

On January 3, 2026, the U.S. forces launched a surprise strike inside Venezuela and forcibly removed President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, flying them to New York to face the U.S. charges. Reports described explosions in Caracas and the Maduro Government denounced an “imperialist attack” on national sovereignty. President Trump boasted on social media that the strike was carried out “in conjunction with U.S. law enforcement,” heralding Maduro’s capture as a triumph.

The world responded with alarm. Venezuela’s interim Vice President, Delcy Rodríguez, demanded proof that the couple was alive. Russia and China voiced their strongest objections. Japan stressed the safety of its nationals, reaffirmed its commitment to “freedom, democracy, and the rule of law,” and indicated that it would work with G7 partners to help stabilise the region, while India expressed “deep concern” and reaffirmed support for the security of the Indian community and the people of Venezuela. Even within the United States, Secretary of State Marco Rubio acknowledged at a press briefing that Congress had not been consulted.

These events raise stark legal questions. The core issues are jus ad bellum limits on the use of force, the prohibition on intervention and extraterritorial enforcement jurisdiction, the personal immunities of incumbent senior officials, and the consequences if the incursion triggered an international armed conflict. U.S. constitutional processes and the War Powers Resolution may constrain American decision-makers as a matter of domestic law, but they do not alter Venezuela’s rights under international law.

Armed Assault or Law Enforcement Operation?

Under the U.N. Charter, no state may unilaterally use military force against another except with Security Council approval or genuine self-defense. The US administration claims this was a cross-border “law enforcement” operation, but international law treats armed assaults like this as uses of force. As one expert summary notes, counter-narcotics or “illegitimacy” justifications cannot override Article 2(4)’s prohibition. Legal scholars agree that drug trafficking, even if a global scourge, is a criminal matter, not an armed conflict that justifies invasion.

Customary international law adds another dimension: sitting heads of state have absolute immunity from arrest by foreign courts. Under the Arrest Warrant case and related practice, Maduro, as the incumbent Venezuelan President enjoys complete “inviolability” from forcible seizure. The U.S. might say it no longer recognises Maduro as legitimate, but international law does not allow one country to strip another’s leader of all protection while still holding it to its obligations. Even if Washington claims Noriega-like precedent, “unilateral kidnapping is unlawful regardless of recognition, and immunity questions aggravate, rather than cure, the illegality.”.

Likewise, the principle of non-intervention is clear. “Cross-border apprehension” by force without the host state’s consent is an “unlawful exercise of enforcement power”. By sneaking in Marines or special ops to snatch Maduro, the U.S. bypassed all Venezuelan authorities and UN mechanisms. It also bypassed its own procedures by not informing Congress. As France’s foreign minister noted, the U.S., a Security Council member violated the principle of non-use of force and imposed an external solution, warning that “no sustainable political solution can be imposed from the outside”

By employing bombs and missiles on Caracas, the operation arguably triggered an international armed conflict between two states. If so, the full body of international humanitarian law (IHL) applies. Every strike must meet IHL’s distinction and proportionality tests. For example, reported strikes that knocked out civilian power infrastructure would be illegal if the civilian harm outweighed any military gain. Moreover, once Maduro was captured, he became a protected person under the Geneva Conventions. He and his wife would be entitled to safe detention conditions and eventual release or trial, but under domestic law, not as prisoners of war. Importantly, even the abduction itself violates the duty to take “prisoners” only lawfully.

In practical terms, neither side seems prepared to declare war, but the weapons used leave no doubt: the U.S. struck fixed targets with lethal force on foreign soil. Still, any escalation (for example armed skirmishes with Venezuelan forces) would immediately invoke full wartime protections.

The Maduro abduction cannot be seen in isolation. In recent years, permanent members of the UN Security Council have repeatedly tested, stretched, or disregarded legal constraints: China has rejected the legal effect of the South China Sea arbitral award; Russia’s conduct in Ukraine has triggered sustained allegations of Charter breach; and the United States has its own history of unilateral uses of force, including the closely analogous 1989 intervention in Panama (Operation Just Cause).

Each episode erodes confidence that treaties and the Charter’s restraints bind the most powerful as much as the rest. The United States is central to this story not only because it helped design the post-1945 order and was among the earliest to ratify the Charter, but also because its subsequent engagement with the UN’s treaty architecture has been selective. This is illustrated by continued non-ratification of major UN-linked instruments such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Those choices do not reduce UN Charter obligations, but they sharpen doubts about commitment to the wider treaty-based project the UN Charter was designed to anchor.

Unsurprisingly, the fiercest reaction came from Russia and China. After a China‑sponsored UNSC emergency session, several members condemned the raid as illegal, echoing concerns about a dangerous precedent. Russia’s Foreign Ministry condemned the raid online as “an act of armed aggression.” Intriguingly, France’s envoy reminded that any UN Security Council permanent member breaking the force ban would have “grave consequences for global security”. The cumulative message is clear: when the great powers act unilaterally, the treaty-based system frays. Skeptics will ask whether the U.N. framework can survive if its core rules are flouted. Does international law still constrain might, or have we entered a world where the strongest simply write the rules as they go? The Venezuela case forces a stark choice. If states like the U.S. can repackage aggression as policing, the Charter’s promise is hollow. Yet abandoning the treaty model risks slide back into unchecked power politics. This episode does not resolve the dilemma, but it raises it emphatically: If the rules won’t hold strong, what will? The international community now must grapple with whether to reinforce the existing treaty-based UN order or to forge new legal or political instruments. Will “law enforcement” become a blank check for regime change, or will this bold act prompt a rethinking of how global security is governed? The answer is not yet clear, but the question can no longer be ignored.