Forced labour, servile marriages, bonded inhuman labour, physical torture and abuses against women, children and the elderly have threatened Sindh’s minorities.

I. Executive Summary

Debt bondage in Sindh is systemic, inter-generational and structurally embedded. Legal prohibitions and international commitments notwithstanding, serious gaps in enforcement and socioeconomic inequalities sustain a cycle of exploitation. Without coordinated, evidence-based and politically accountable reform, millions of minorities, women and children remain at risk of continued slavery.

Scale of Crisis

- An estimated 2.35 million people in Pakistan live in conditions of modern slavery (Global Slavery Index 2023) with debt bondage being a key issue.

- Pakistan ranks among the highest globally in absolute number of people in modern slavery.

- Sindh is one of the most affected provinces, particularly in agriculture and brick kilns.

Debt Bondage in Sindh

- Workers accept advance loans (peshgi) under exploitative conditions that make repayment nearly impossible.

- Debts are often undocumented, inflated through arbitrary interest and transferred across generations.

- Entire families, including women and children, are bound to landlords or kiln owners.

- Bondage operates as a system of hereditary labour entrapment and not temporary indebtedness.

High-Risk Districts & Sectors

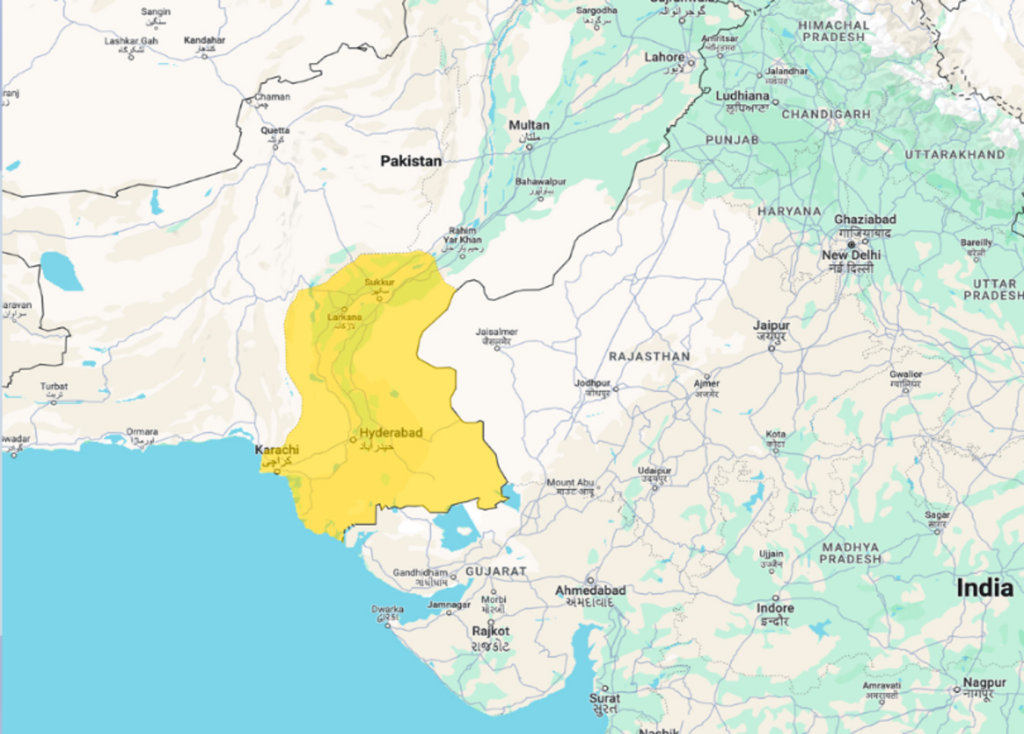

- Districts such as Tharparkar, Umerkot, Sanghar, Mirpurkhas, Badin and Thatta are particularly vulnerable.

- Most affected sectors include:

- Agriculture (sharecropping / haris)

- Brick kilns

- Informal and cottage industries

Impact on Minorities

- Hindus constitute approximately 8–9 per cent of Sindh’s population, with Scheduled Caste (Dalit) Hindus heavily concentrated in rural districts.

- Minorities, particularly low-caste Hindus, are large in numbers among bonded labourers due to entrenched socioeconomic and caste-based marginalisation.

- Women and children in minority households face compounded vulnerabilities, including forced labour and early entry into exploitative work.

Child Labour Dimension

- The Sindh Child Labour Survey (2022–24) estimates over 1.6 million children engaged in hard labour with around 800,000 in hazardous conditions.

- Bonded labour systems frequently trap children in intergenerational debt cycles.

- US Department of Labour reports continue to identify forced labour in brick kilns and agriculture.

Legal and Policy Gaps

- The Sindh Bonded Labour Abolition Act (2015) provides a legal framework but enforcement remains weak.

- District Vigilance Committees are largely inactive.

- Investigations, prosecutions, convictions and rehabilitation data remain limited and fragmented.

- Pakistan has committed to Sustainable Development Goals target of 8.7 (ending modern slavery by 2030), yet progress remains insufficient.

- This makes Pakistan a potential case for possibly not meeting its commitment made under United Nations charter to wipe out slavery in next four years

Structural Drivers

- Feudal landholding patterns concentrate economic and political power.

- Informal labour contracts and lack of financial inclusion push vulnerable families into exploitative advances.

- Weak governance, political patronage networks and limited accountability perpetuate impunity.

Challenges in Rehabilitation & Reintegration

- Freed bonded labourers often lack:

- Access to land or alternative livelihoods

- Legal support for restitution

- Social protection and reintegration assistance

- Rescues reflect scale rather than systemic resolution.

Human Rights Relevance

- Debt bondage violates protections against slavery and forced labour.

- It undermines children’s rights, fair working conditions and access to legal remedies.

- Sustained monitoring, technical assistance and data-driven engagement are critical at both national and international levels.

II. Context

Debt bondage, a contemporary type of slavery wherein employees are obligated to their employers against unpaid advances and structural pressure, remains deeply ingrained in Sindh’s rural economy. It continues to be one of the most pervasive yet under-addressed human rights issues. Statutory prohibitions notwithstanding, international commitments and constitutional protections, exploitative practices continue unhindered due to systemic socioeconomic and governance failures, trapping millions of people in debt bondage, forced labour and coercive exploitation across important economic sectors.

Minorities, especially low-caste Hindus, are disproportionately affected by cycles of inequality and exploitation perpetuated. Millions of people are still working in bonded labour in agricultural, brick kiln and informal sectors, according to extensive data and field reports. Minorities are disproportionately affected due to socio-cultural marginalisation.

III. Background:

Sindh, one of the world’s oldest centres of civilisation, is home to the Indus Valley and has historically served as a hub for ideas, trade and cultural development. The region’s multi-layered history, which includes Persian, Afghan, Mughal and eventually British colonial dominance, illustrates both cultural richness and repeated conquest from Mauryan, Kushan and Gupta rule to its significance as a centre of Islamic study and trade under Arab and Turkic rulers.

Sindh has struggled with persistent concerns about political centralisation, unequal resource distribution and influences on its linguistic and cultural identity ever since it joined Pakistan in 1947.Discussion about representation, economic justice and provincial autonomy is still essential for understanding current conflicts and the Sindhi movement’s desire for increased involvement in choices affecting the future of the area. Owing to mistreatment and mismanagement, there have been persistent demands for complete independence as a sovereign Sindh nation.

As of 2023, Sindh, one of Pakistan’s four provinces, is home to an estimated 55 million people and occupies 140,914 square kilometres. In addition to serving as the provincial capital, Karachi is the biggest metropolis and centre of Pakistan’s economy. English is commonly used in government, administration and education, whereas Sindhi is the official provincial language and Urdu is the national language.

Due to Sindh’s historically complex social fabric, majority of the province is Muslims (around 91 per cent) with Hindus making up the largest religious minority (about eight per cent).

World Sindhi Congress (WSC), which represents Sindh abroad at Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organisation (UNPO), promotes Sindhi political, cultural and human rights concerns on a global platform.

Sindh has a long history of civilisation that dates back to ancient times. The ancient homeland of the Sindhu (Indus) River is known as Sindhudesh or Sindhu Kingdom in Mahabharata. Sindh’s longstanding status as a unique cultural and political entity in early South Asian history is reflected in the name.

Sindhi people face increasing environmental, socioeconomic and human rights challenges that require immediate international attention. The targeting of ethnic Sindhis and religious minorities, together with reports of enforced disappearances, extrajudicial executions and dissent repression, highlights a very alarming accountability vacuum.

Religious prejudice has escalated, making minority groups, especially Hindu girls, more susceptible to kidnapping and coerced conversion. Simultaneously, Sindh’s agrarian economy has been severely damaged by climate vulnerability, rising sea levels, soil salinity and frequent flooding.

Economic Corridor (CPEC) have accelerated ecological degradation, industrial pollution and displacement without sufficient local consultation. Sindh’s socioeconomic stability and cultural security have been undermined by these intertwined crises that have strengthened calls for greater political representation, minority rights protection, environmental protection and meaningful involvement in decisions that impact the region’s resources and future development.

IV. Debt Bondage: A Silent Killer

Debt bondage also known as bonded labour is contemporary form of slavery. It happens when someone is forced to pay back debt or advance payments (commonly referred to as peshgi) on terms that make it nearly difficult to comply due to exorbitant interest rates and pitifully low salaries.

They are unable to refuse or flee exploitative labour which traps workers and their families. Forced labour, human trafficking, servile marriage and bonded labour are all considered forms of modern slavery and are included in the Global Slavery Index framework.

On paper, millions of Sindhis in Pakistan enjoy freedom, but in practice, bondage rules their lives. Debt is a multigenerational trap designed to keep an indigenous community economically reliant, socially immobile, and politically silent in rural Sindh. It is not a short-term misery.

Poverty is not the cause of this. It is a social order that was created.

Districts where agriculture and kiln-based labour dominate local economies, such as Tharparkar, Umerkot, Sanghar, Mirpurkhas, Badin, Thatta and portions of Hyderabad division, are regularly designated as high-risk.

V. Signature Patterns in Sindh

In Sindh, bonded labour is still widely used, especially in brick kilns and agriculture, where unskilled labourers and landless peasants (haris) take advance loans from kiln owners or landowners and get caught in never-ending debt cycles that last for generations.

Farmers are frequently forced to give up a disproportionate amount of their produce due to informal and opaque sharecropping arrangements, which increase their financial dependence and restrict any feasible route to repayment. Importantly, bonded labour is not limited to adult male workers; women and children are also ensnared in household debt commitments, making them more susceptible to abuse, exploitation and systematic denial of their basic rights. These obligations are:

- undocumented or fraudulently recorded

- inflated through arbitrary interest

- transferred from parents to children

A Sindhi child is often born with debts that will never be paid off, including money the child never borrowed and working land he/she will never own. This isn’t labour but ‘hereditary imprisonment’.

VI. Feudal lords get State cover

Persistence of debt bondage in Sindh is due to ingrained structural and socioeconomic factors rather than by chance. Vulnerable families are forced into exploitative advance loans (peshgi) by chronic rural poverty and exclusion from conventional banking systems, which bind them to creditors before their first day of work even starts. This dependence is further cemented by feudal landholding patterns, which maintain coercive sharecropping arrangements and concentrate economic power in the hands of wealthy landlords.

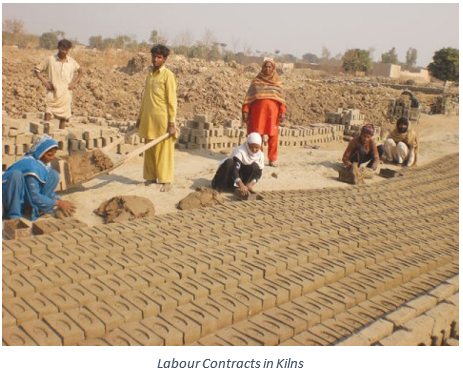

Labour contracts in informal economy, especially in small-scale farms and brick kilns, are unwritten and uncontrolled, leaving workers without legal protections as debt mounts covertly. Despite the fact that the Sindh Bonded Labour Abolition Act (2015) establishes a legal framework for protection, the system has remained largely unchallenged, resulting in a generational cycle of exploitation due to lax enforcement, inadequate monitoring and inert District Vigilance Committees.

Large landowners, many of whom are part of federal and provincial political structures, serve as

- Employers

- Creditors

- Middlemen in local law enforcement

- Vote brokers.

Police rarely step in. Courts are slow. Rescue operations are symbolic. Sindhis are subject to violence, re-capture or criminalisation should they try to escape bondage. The law exists. Justice does not.

VII. Prevalence of Modern Slavery in Pakistan: National Estimates

- The Global Slavery Index 2023 (GSI 2023) estimates that in 2021, there were 10.6 modern slaves per 1,000 inhabitants in Pakistan or around 2,349,000 persons.

- In terms of the prevalence of modern slavery, Pakistan is ranked at number four in the Asia-Pacific area and 18th globally.

As per GSI 2023, forced labour, forced marriage and debt bondage are all considered forms of modern slavery. Although the Index offers national statistics, provincial breakdowns, including Sindh estimates, are not published by it. However, because of particular socioeconomic circumstances, Sindh is one of the primary areas where debt bondage is concentrated, according to national data and civil society surveys.

VIII. Civil Society & Field Data

- Hari Welfare Association’s State of Peasants’ Rights in Sindh 2023 report states that at least 12,116 bonded labourers, including women and children, were released from long-term debt servitude in Sindh between 2013 and 2023.

- 542 peasants (185 children, 178 women, and 179 adults) were reported to have been released from bonded labour arrangements in 2023 alone.

- These numbers represent recorded rescues rather than the overall occurrence, which is probably much higher due to underreporting and access issues in rural areas.

IX. Limitations & Data Gaps

Although the Global Slavery Index 2023 offers reliable national prevalence figures, the public dataset does not include particular provincial prevalence percentages for Sindh. Consequently:

- To understand the extent of modern slavery in Pakistan, national estimates have been used as a proxy context.

- Rather than using direct prevalence rates, sectoral studies, civil society reports and documented rescues are used to understand Sindh’s burden.

- Since household surveys do not account for sizable portions of rural and informal labour, localised surveys and advocacy data are crucial to estimating genuine province prevalence.

Cycles of debt and forced labour are sustained by feudal regimes, informal labour agreements and structural economic instability.

| Aspect | Key Estimate or Fact |

| Pakistan’s modern slavery prevalence (GSI 2023) | 10.6 per 1,000 people (2.35 million people) |

| Debt bondage is the leading form of exploitation | Recognised as a core form of modern slavery in rural Sindh & Punjab |

| Sindh’s situational profile | Persistent bonded labour in agriculture, brick kilns, and cottage sectors |

| Impact on women & children | Widely documented, often intergenerational |

Globally, sectors with the highest incidence of forced labour are:

- Domestic work: 24%

- Construction: 18%

- Manufacturing: 15%

- Agriculture and fishing: 11%

In Pakistan specifically, the United States Department of Labor (US DOL) has identified forced labour in:

- Brick kilns

- Carpet weaving

- Coal mining

- Agriculture (cotton picking, wheat, sugarcane)

According to US Department of Labour statistics, child domestic workers are especially exposed to the pervasiveness of forced domestic employment, which is frequently connected to human trafficking.

Pakistan is making only “moderate progress” against child labour and forced labournationwide, according to the US DOL’s 2024 and 2023 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labour. The report highlights the persistence of hazardous work and debt bondage, particularly in the brick and agricultural industries, which are important sectors in Sindh where bonded labour is concentrated. Nearly 700,000 children in Sindh are expected to be working as bonded labourers in agricultural and associated industries, according to assessments previously published by the US DOL, even though the most recent official data from the US DOL does not include precise province-level figures for 2025.

Independent provincial data further highlights the magnitude of the problem. According to the Sindh Child Labour Survey (2022-24), over 1.6 million children (roughly 10.3% of those aged 5-17) are involved in child labour throughout the province, with about 800,000 of them working in dangerous and exploitative conditions that overlap with debt bondage systems in rural economies. These numbers show that despite current laws and policy measures, bonded and forced labour, which particularly affects children caught in generational debt, remains a serious human rights and labour protection issue in Sindh.

X. Sectors Most Affected

- Agriculture (Haris / Sharecroppers)

| Haris/ Sharecroppers in Agriculture Sector |

Approximately 43% of Pakistan’s workforce is employed in agriculture, which is still primarily an unorganised sector. Landlords frequently give advances to landless peasants (haris) in Sindh to cover emergencies or subsistence expenses. These loans, which bind entire families to landlords for generations, are rarely properly documented and are frequently structured in ways that make repayment impossible.

| Bonded Labour in Sindh Brick Kiln |

Brick Kilns

One of the most well-documented locations of bonded labour in Sindh is brick kilns. Cash advances are used to recruit families, who are then forced to labour under duress, which includes:

- Withholding of wages

- Mobility Limitations

- Debt “sale” or transfer between kiln owners

In order to pay off accrued debt, children often work alongside adults.

XI. Rehabilitation and Data Deficits

In Sindh, freed bonded labourers usually lack:

- Availability of land or other sources of income

- Legal assistance to ensure accountability or restitution

- Assistance with reintegration and social protection

| Bonded Labour Trapped in Poverty |

Furthermore, there is still a dearth of trustworthy, broken-down data on bonded labour in Sindh that covers identification, prosecutions, convictions and rehabilitation results. This severely limits the creation, oversight and accountability of policies.

XII. Relevance to UN Engagement

Concerns are raised by Sindh’s continued use of bonded labour under:

- Outlawing forced labour and slavery

- The right to fair and comfortable

working conditions

- The rights of children

- Legal equality and a practical cure

Addressing one of the most pervasive forms of modern slavery in Pakistan requires targeted attention to Sindh through monitoring, technical assistance, and data-driven engagement.

| Hindus (Dalit) Bonded Labour in Pakistan |

XIII. Disproportionate Harm to Minorities: Focus on Hindus

Demographic Vulnerability

- Hindus constitute approximately 8.8% of Sindh’s population, with scheduled caste (Dalit) Hindus making up a significant sub-group highly concentrated in rural districts like Umerkot, Tharparkar, Sanghar, and Mirpurkhas.

- Historically, socioeconomic and caste-like discrimination have overlapped for Dalit and low-caste Hindus, increasing their susceptibility to debt bondage.

Disproportionate Prevalence

- Research indicates that Dalits and tribal minorities make up the bulk of bonded agricultural labourers in southern Sindh, and their poverty forces them to take advantage of landlords’ advances.

- Due to institutional marginalisation and limited access to legal recourse, historical and scholarly research shows that minorities, especially low-caste Hindus, are disproportionately represented among bonded labourers.

Commitments vs. Implementation Gaps

- One of the Sustainable Development Goals that Pakistan is a party to is SDG 8, Target 8.7, which calls on governments to eradicate child labour, forced labour, modern slavery and human trafficking by 2030. But there hasn’t been any progress.

- Although there are laws that make modern slavery illegal, reliable information about investigations, prosecutions, and convictions is hard to come by. Policy responses are fragmented, and accountability is weak in the absence of an empirical base.

Comparative Context

Pakistan vs. Regional Patterns

• According to the European Union Agency for Asylum, Pakistan has one of the highest rates of modern slavery in Asia, with an estimated 3–4.5 million victims.

• Sindh’s bonded labour dynamics are similar to those found in the Caribbean, Africa and South Asia, where racially stratified, caste or ethnic minority labour systems continue to exist despite official abolition laws.

Gender and Child Dimensions

- Women and children make up more than 70% of bonded labourers in industries including agriculture and brick kilns, suggesting that bondage is perpetuated in a gendered and intergenerational manner.

| Children & Women as Bonded Labourers |

This factor is especially noticeable in minority households when children are put into labour at a young age to pay off family obligations.

XIV. Pakistan in the Global Slavery Index

| Year | Estimated People in Modern Slavery | GSI Rank |

| 2014 | 2.0 million | 6th |

| 2018 | 3.19 million | 8th |

| 2023 | 2.3 million | 4th highest absolute numbers |

- Pakistan routinely ranks among the top nations for the prevalence of modern slavery.

- The most prevalent type of modern slavery is still debt bondage.

XV. Multi-Faceted Response

To eradicate contemporary slavery, prevention, protection and rehabilitation must be addressed concurrently, treating the underlying causes as well as the symptoms.

Among the top priorities are:

Extend Social Protection: The ILO has suggested that social protection be extended to the unorganised sector. Important strategies for mitigating debt-induced bondage include cash transfers (BISP, Khidmat Card), public employment programs, health protection plans (Sehat Card, Sehat Insaf Card) and ethical microfinance projects (e.g., Akhuwat).

Formalise High-Risk Sectors: Labour regulations, particularly the simplification of tenancy rules, should be extended to the agricultural sector. Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa must follow Sindh and Balochistan’s lead in allowing agricultural and fishing workers to form unions.

Another high-risk industry that urgently needs legislation is domestic work. Child domestic employment ought to be classified as dangerous and forbidden for anyone younger than eighteen.

Strengthen Migration Governance: Trafficking and migration are strongly related to modern slavery. Given the high number of Pakistanis employed overseas, especially in the Middle East, Pakistan has to pursue legally enforceable bilateral labour agreements that guarantee respectable working conditions in addition to pre-departure instruction.

Reform Labour Laws: Since wage withholding is the most widely used type of coercion, labour laws should make it illegal to fail to pay wages, unless there are specific legal restrictions. All industries must have equal access to labour safeguards.

Revitalise Local Enforcement: To assist in the discovery, rescue and rehabilitation of bonded labourers, district vigilance committees that are presently inactive or inert must be reinforced and connected to local governments.

Build a National Evidence Base: One of the key challenges is still the lack of trustworthy, de-identified data. Tracking investigations, prosecutions and results requires improved research, data collection and interdepartmental information exchange.

XVI. Concluding Observations

With deep socioeconomic roots and insufficient legislative remedies, debt bondage in Sindh continues to be a systemic human rights concern. As per official estimates, millions of people are still trapped, but minorities, particularly Hindus from lower castes are disproportionately exposed to and suffer from compounded harms as a result of intersecting discrimination. In addition to enforcing the law, this calls for revolutionary actions that upend the socioeconomic structures that support modern slavery.

An estimated 2.35 million people in Pakistan are thought to be living in modern slavery, with financial bondage playing a significant role in this catastrophe, according to the Global Slavery Index (2023). Sindh is one of the most badly impacted areas of the country, especially in the brick kiln and agricultural sectors, where long-standing advance-loan schemes force whole families into abusive work contracts. Due to feudal landholding patterns and informal labour structures, field research and independent reporting repeatedly show that rural Sindh is a major centre for bonded labour. Thousands of bonded workers have been freed over the years thanks to the efforts of civil society organisations, but these rescues highlight scale rather than resolution, exposing a deeply ingrained system that perpetuates poverty, dependency and generational exploitation in vulnerable communities.

In Pakistan, modern slavery is systematic, predictable and avoidable; it is neither unintentional nor invisible. Millions will continue to be caught in cycles of exploitation unless decisive, well-coordinated and evidence-based action is taken. The goal of ending modern slavery by 2030 is not just a worldwide pledge; it is also a test of Pakistan’s capacity to make legal promises a reality.

XVII. References:

- Baloch, M. (2024, August 23). Labour in chains. The Express Tribune. https://tribune.com.pk/story/2492077/labour-in-chains

- Dawn Editorial. (2024, September 2). Bonded labour in Sindh. Dawn. https://www.dawn.com/news/1855158

- Hari Welfare Association. (2023). State of peasants’ rights in Sindh 2023: Debt bondage remains pervasive across Sindh despite legislation. https://hariwelfare.org/state-of-peasants-rights-in-sindh-2023-report-launch-debt-bondage-remains-pervasive-across-sindh-despite-legislation/

- Hari Welfare Association. (2023). Hari report 2023 (Draft 5 Final). https://hariwelfare.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Hari-Report-2023-Draft-5-Final.pdf

- Walk Free. (2023). Global Slavery Index 2023. Walk Free Foundation. https://www.walkfree.org/global-slavery-index/

- Walk Free. (2023). Global Slavery Index 2023: Pakistan country snapshot. Walk Free Foundation. https://cdn.walkfree.org/content/uploads/2023/09/27164917/GSI-Snapshot-Pakistan.pdf

- The Express Tribune

- Business Recorder

- US Department of Labor

- The Economic Times

- World Bank

- Human Rights Watch

- AsiaNews

- Geo News