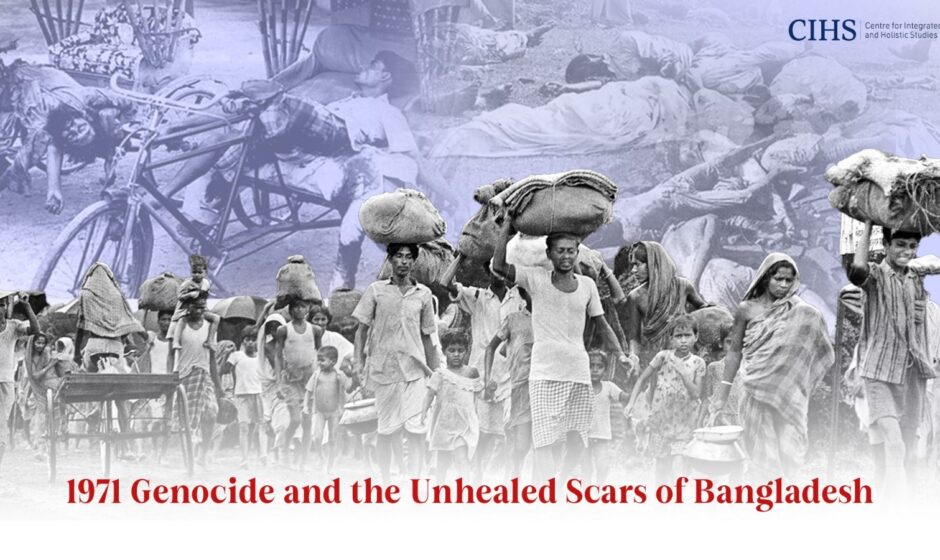

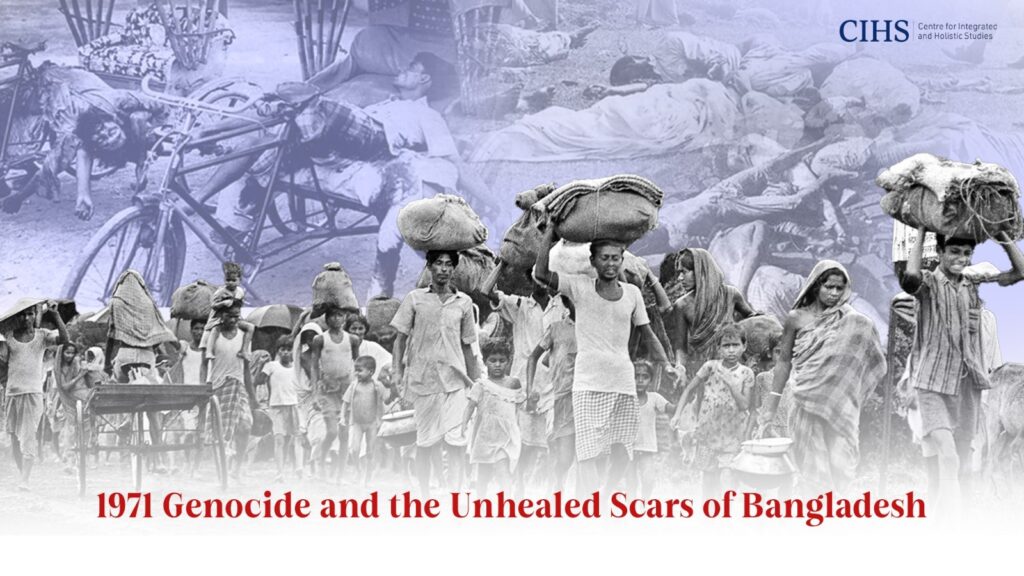

Bangladesh may paper over its wounds one by one, but the scars of systematic genocide during 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War will remain permanent.

Pummy M. Pandita

The 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War was marked by a systematic campaign of genocide carried out by the Pakistan Army and its supporting forces, Razakars, against the Bengali population, pro-independence activists, intellectuals and civilians. The Razakar Force, officially established by the Pakistan Army under the command of General Tikka Khan and acknowledged as a proxy paramilitary entity, was pivotal in the perpetration of these offenses at the direct command from Pakistan. More than fifty years post-independence, Bangladesh persistently pursued international acknowledgment and a formal apology from Pakistan; however, these requests remain unmet. The enduring impact of violence and denial has resulted in lasting sociopolitical wounds that continue to manifest in both domestic and diplomatic contexts.

Established pursuant to the East Pakistan Razakars Ordinance issued in August 1971, this militia group was intentionally created to serve as a local support mechanism for Pakistan’s counter-insurgency efforts against the Bengalis of erstwhile East Pakistan. The establishment and functioning of this militia group were crucial to the genocidal tactics employed by the military leadership of Pakistan in order to stifle the aspirations for independence from Pakistan.

The contingent comprised roughly 50,000 volunteers, primarily sourced from Islamist groupings in Pakistan political groups including Jamaat-e-Islami, Al Badr, Al Shams and others that resisted Bengali autonomy.

In stark contrast to purported accounts, the Razakars were not merely engaged in “internal security” operations; they were complicit in heinous acts of mass murder, sexual violence, torture and terror directed at civilians, with a particular focus on Hindu communities, political dissidents, scholars and advocates for independence from Pakistan.

After the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, approximately 200,000 women and girls, predominantly Hindus, were raped by the Pakistani Army and its allied proxies (Razakars). These heinous acts were part of an effort to create a “pure” Muslim race in Bangladesh. The targeting of Hindu women has continued, with sexual violence being used to intimidate and displace Hindu families. Multiple thoroughly recorded massacres during 1971 by Razakars alongside the Pakistan Army, encompassing extensive killings in Jathibhanga (approximately 3,000–3,500 victims), Gabha Narerkathi (95–100 Hindu victims), Akhira and Char Bhadrasan, among others, each exemplifying methodical assaults on defenseless populations.

In December 2019, almost fifty years post Bangladeshi independence, the Government of Bangladesh released an official enumeration of 10,789 individuals recognized as Razakars, a clear initiative to identify and document those who supported the Pakistan Army’s operations against the Bengali population. The aim was to guarantee that future generations retain awareness of the genuine perpetrators of violence and treason, opposing any efforts to obscure or sanitise this historical narrative.

Notwithstanding these actions, the pursuit of justice remains unfulfilled and the scars of history endure.

The lack of an official apology transcends mere diplomatic obstruction; it signifies a refusal to acknowledge historical responsibility, thereby exacerbating the anguish of survivors, the families of victims and the broader communities deeply affected by the events of 1971. For a significant segment of Bangladeshi society, especially among Hindu communities that were disproportionately targeted, the ongoing lack of recognition constitutes not merely an omission but a deliberate erasure. It denies victims and survivors both justice and historical recognition, making their suffering invisible and original crimes even worse. This silence reinforces impunity, invalidates experienced trauma and indicates a systemic reluctance to address the violence perpetrated by Razakars and Pakistan Army against these communities.

The Razakar legacy stands as a profound and enduring mark in the collective consciousness of Bangladesh, serving as a proof to the genocidal tactics employed by the Pakistan Army and its accomplices. It highlights the necessity for healing from mass atrocities, which hinges on the pursuit of truth and formal accountability, elements that cannot be fully achieved without clear recognition and apology from those who hold historical responsibility.

The plight of Hindu communities in present-day Bangladesh finds its roots in the tragic events of the 1971 Liberation War and this suffering has persisted in a sporadic manner throughout the subsequent decades. In the year 1971, the Pakistan Army, in conjunction with the Razakars, engaged in state-sanctioned violence that resulted in widespread atrocities, including mass killings, sexual violence and the deliberate persecution of the Hindu community as a distinct religious group. The immediate consequences resulted in significant refugee movements and a sustained demographic reduction of Hindus in Bangladesh. Since the attainment of independence from Pakistan, there has been a recurring pattern of communal violence, biased governance practices, assaults on property and places of worship and a prevailing sense of impunity for those who commit such acts. This troubling trend has notably escalated during periods of political instability in 2024–25, resulting in cycles characterised by fear, displacement and the erosion of rights.

Historical context: targeted violence in 1971

“Operation Searchlight” on March 25, 1971, started the Bangladesh Liberation War, which lasted from March to December 1971. The campaign conducted by the Pakistan military specifically aimed at Bengali freedom fighters, scholars, students and, with notable intensity, Hindu civilians. Recent and ongoing research show that there were coordinated mass executions, gang rapes used as weapons against women (especially Hindu women) and communal cleansing in towns and rural areas where Hindus lived. Independent scholarly reviews, government compilations of incident reports and survivor testimonies delineate massacres nationwide, enumerating particular incidents with substantial civilian casualties. Scholars and post-war accounts emphasise that although Bengalis were the primary targets, Hindus were subjected to extreme brutality due to their perceived political and cultural alignment with India and the Bengali freedom struggle.

The ongoing vulnerability of Hindu communities in Bangladesh from 1972 to 2024 has been perpetuated by a combination of systemic impunity, inadequate legal accountability and politicised justice. Post 1971 period promised justice, but convictions for war crimes were few and far between, allowing many criminals and their networks to become part of local power structures again. Even when accountability mechanisms like the International Crimes Tribunal were used, the idea and practice of selective justice frequently made them less effective at bringing people together. For example, they dealt with symbolic crimes at the national level but ignored everyday violence at the local level. Because of this, the criminal justice system often doesn’t look into or discreetly drops ordinary attacks on Hindus, including arson, land expropriation, forced displacement, temple desecration and targeted intimidation. This persistent inability to prosecute criminals not only indicates institutional frailty but also conveys a message of permissiveness, so fostering recurrent violence and perpetuating fear. Over decades, this pattern has turned short-term persecution into a permanent problem, where insecurity is the norm, complaints go unanswered and the weakness of minorities becomes a permanent part of the post-liberation state instead of an exception.

The political use of religious identity has made Hindu communities even more vulnerable. Instead of being protected as a fundamental right, faith is often used as a tactic for getting people to vote. Over the course of several electoral cycles, leaders have used majoritarian religious emotion to their advantage for short-term political benefit. This has made exclusionary language commonplace and made it easier for minorities to be threatened and attacked. Extremist and fringe groups have used times of government change, election disputes or street protests to assault Hindu neighborhoods, places of worship and livelihoods with little fear of punishment. Adding to this, governmental reactions have frequently been reactive, inconsistent or late, going back and forth between strong words of condemnation and limited enforcement instead of long-term preventive measures. This inconsistency weakens deterrence, makes it harder to hold people accountable and makes it seem like minority protection is up for political negotiation, putting Hindu communities at risk whenever identity politics takes precedence over the rule of law.

Socioeconomic marginalisation and land insecurity have come together to become two of the most common and least talked about causes of violence against Hindu communities. A large number of attacks didn’t happen in the open as communal riots; instead, they happened as property theft, forced eviction and systematic encroachment on temple and community land, often posing as private or administrative disputes. This framing intentionally hides their communal nature, which lets the people who did it take advantage of differences in power, documentation and access to legal recourse. In situations where minorities have weaker land titles, less political support and less institutional protection, land is both the reason for and the weapon of persecution. The lack of strong legal protections and quick decisions makes it easy for these acts to happen, turning economic predation into a way to put pressure on demographics. Over time, these actions did more than just take away people’s property; they changed the geography of the area, made it harder for minorities to get by and made displacement a normal, slow process instead of an unusual form of abuse.

Recent Trends and Acute Crises (2010s–2025)

From the early 2010s to 2025, a consistent collection of records from human rights groups, investigative journalists, civil-society monitors and parliamentary records shows that Hindu communities in Bangladesh have been the victims of violence in a pattern-driven cycle that is closely linked to times of political conflict, electoral instability or religious provocation. These incidents are not isolated occurrences; they indicate a systemic vulnerability that exacerbates during periods of instability, characterised by a decline in state authority and the exploitation of uncertainty by extremist or opportunistic entities. The fact that these kinds of events keep happening in different political cycles shows that constitutional protections are not being turned into real security for minorities.

This trend became very clear in 2021, when international NGOs reported deadly attacks on Hindu festivals and residential areas that involved organised mob violence, widespread arson, desecration of temples and multiple deaths. These groups told the Bangladeshi government to make policing more effective, make sure that people are held accountable quickly and go after the people who did the attacks. These warnings made it clear that the attacks were brutal and that violence like this is likely to happen when tensions are high between communities. The fact that similar patterns have come back since then shows that these suggestions weren’t properly put into practice.

The situation got much worse after the political turmoil in 2024, when international media, rights groups and minority organisations reported a sharp rise in attacks on Hindu homes, businesses and places of worship in many districts. Minority community groups recorded thousands of events in a short period of time and news reports described targeted vandalism, threats and violence that went beyond random unrest. The severity of this wave was so great that parliamentary debates in several foreign legislatures openly questioned Bangladesh’s ability and readiness to protect minorities during political crises. This raised the issue from a failure of domestic governance to an international concern.

Civil society networks, minority councils and independent monitors collected quantitative data in 2024 and 2025. Although the numbers and methods used were different, they all came to the same important conclusion: when there is political instability, there is a sharp rise in violations of communal rights. Even when the numbers are disputed, the overall trend is clear. All of these datasets point to a systemic problem in which mechanisms for protecting minorities fail exactly when they are most needed. This turns political unrest into a recurring cause of communal violence instead of a one-time event.

The ongoing violence against Hindu communities has caused deep, long-lasting harm to people that will last for generations, in addition to the immediate deaths and physical injuries. Repeated attacks have caused number of people to leave their homes, forcing families to move within their own country or flee to India in search of safety and a way to make a living, often at the cost of never being able to return to their ancestral homes. Economic devastation makes this insecurity worse: businesses are destroyed, agricultural land is taken and inherited property is lost through threats or false claims, which hurts people’s livelihoods and wealth that has been passed down through generations. At the same time, the systematic vandalism of temples and interference with religious practice speeds up the loss of culture, making it harder for people to identify with their communities and cutting them off from their historical and spiritual roots. At the heart of all this is deep psychosocial trauma, a result of unresolved sexual violence during the war and repeated attacks on communities. This trauma leaves survivors and whole communities living in constant fear, distrust and mental pain. When you look at all of these effects together, you can see that the damage done is not temporary but long-lasting and structural, changing demographics, livelihoods and cultural continuity long after each event is no longer in the news.

The ongoing violence against Hindu minorities is best understood not as a series of isolated incidents, but as the result of systemic failures that keep happening over and over again. During times of political change or when there is a fight for power, there is a clear security–governance gap. Local power brokers, criminal networks, and angry mobs take advantage of the temporary loss of state control, and minorities suffer the most. This was very clear during the political crisis of 2024. This vulnerability is exacerbated by selective accountability and instrumentalised justice: when legal processes are viewed as politicised or inconsistently enforced, deterrence fails, reprisals remain unpunished and impacted communities lose confidence in formal remedies. Adding to this are institutional bias and administrative neglect, which make it harder for minorities to get ahead in places where the interests of the majority are more important than those of the minority. This is especially true in places where the interests of the majority are more important than those of the minority.

Emergence of extreme Islamist outfits such as Jamaat-e-Islami and Hefazat-e-Islam in Bangladesh’s political setting cannot be ignored. These organisations have documented history of campaigning for policies that oppress minorities and undermine the concept of secularism. These outfits have used political turmoil to promote their interests at the cost of minority oppression.

To help Hindu minorities in Bangladesh who are already very vulnerable, practical steps based on evidence that go beyond just talking about it are required to be taken. At the state level, authorities must publicly reaffirm and operationalise a zero-tolerance policy toward communal violence, anchored in rapid and independent investigations, transparent prosecutions and publicly accessible case records that restore deterrence and credibility. Legal protection must be fortified in areas where harm is most prevalent, land and property, by implementing expedited dispute resolution mechanisms for properties seized or contested under communal pressure. Preventive security is just as important. Unbiased, planned protection for festivals and places of worship, working directly with local minority leaders, can stop flashpoints from happening before violence breaks out.

Concluding Observations

The violence experienced by Hindu communities in Bangladesh is rooted in the historical trauma of genocide of minorities in Bangladesh, especially during and after the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War. Deliberate persecution of Hindus throughout the conflict and ensuing appropriation of land under the Vested Property Act have left a lasting impact on the community, leading to their uprooting and economic marginalisation and is perpetuated by a current amalgamation of political instability, inadequate accountability and exclusionary narratives. It’s not just a problem with the past; it’s a problem with how things are run right now. Any lasting response must work on three important fronts at the same time: fair justice for past crimes, strong protection and quick action against current threats and major changes to the way things are done to get rid of the reasons for communal dispossession, intimidation and violence. For policymakers and civil society, the goal cannot be merely reactive crisis management; it must be the institutionalisation of minority rights as an essential aspect of the rule of law and a measure of democratic resilience, guaranteeing that protection is systemic rather than dependent on political circumstances.

(Author is head of operations at Centre for Integrated and Holistic Studies, a non-partisan think tank based in New Delhi)

References:

Bengali Hindu Genocide Research Centre

(https://bengalihindugenocide.org/overview/perpetrators/?)

The Indian Express

The Sunday Guardian:

SAI, Columbia

SAGE Journals (https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/20578911231207711?)

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Bangladesh

The Caravan: https://caravanmagazine.in/essay/blood-water?

Reuters

The Times of India

Christ University Journals

(http://journals.christuniversity.in/index.php/artha/article/download/2818/1862/5312)