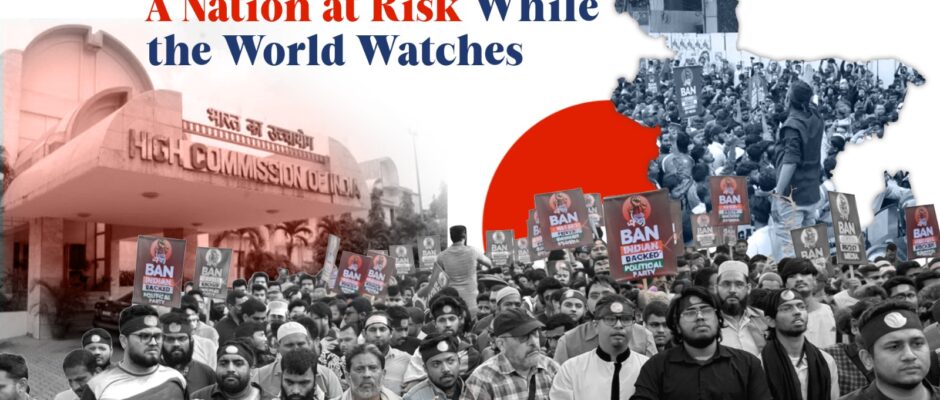

Hindu Pogrom Under a Nobel Laureate’s Watch in Bangladesh

Ethnic Cleansing of Bangladeshi Hindus A Nobel Peace Prize is not a shield against scrutiny. Bangladesh’s post-August 2024 reality demands a hard, evidence-led assessment: violence against Hindus has escalated into a pattern that aligns with internationally recognised elements of ethnic cleansing. This is not a claim made lightly, nor is it built on rhetoric. It is grounded in documented indicators that appear repeatedly across historical cases, from the Balkans to Rwanda and the forced flight of Kashmiri Hindus. Our report, “Hindu Pogrom Under a Nobel Laureate’s Watch in Bangladesh,” examines what changed after the extra-constitutional transition that installed Muhammad Yunus as head of the interim administration. In the immediate aftermath of Sheikh Hasina’s ouster, Hindu homes and temples were specifically targeted, and minority families attempted to flee toward India. This is the first stage seen in many ethnic cleansing trajectories: a sudden collapse of security, followed by identity-targeted attacks that signal “you are not safe here.” Reuters reporting captured these early markers, including vandalism of Hindu temples and homes and attempted flight by minorities. Ethnic cleansing is defined less by slogans and more by method. The method in Bangladesh is visible through six elements. Forced displacement is the predictable output when a minority is subjected to sustained terror and sees no credible protection from the state. When families attempt to flee, when communities retreat into guarded enclaves, when daily life becomes a risk calculation, the displacement is no longer voluntary. It is coerced Violence and terror form the second element. The pattern includes killings by shooting, hacking, abduction, lynching, and arson. The purpose is not only to kill, but to send a message to all remaining members of the community. Dipu Chandra Das’s lynching and burning is an emblematic example of violence designed to intimidate, not merely to harm. Deliberate attacks on civilians are the third element. The victims are not combatants. They are teachers, traders, community leaders, elderly couples, workers, and youth. They are targeted in homes, workplaces, and transit routes, consistent with identity-based selection rather than incidental crime. In the first post-ouster phase, minority groups documented attacks on Hindu homes and temples across multiple districts, underscoring organised targeting rather than isolated incidents. Destruction of property is the fourth element, and it is a strategic tool. Burning homes, looting businesses, and desecrating temples do more than punish. They make return difficult, erase cultural presence, and collapse economic survival. These are classic “remove the population by destroying the conditions of life” tactics. Reuters recorded that hundreds of Hindu homes and businesses were vandalised and multiple temples damaged during the initial post-ouster violence. Confinement is the fifth element. Even without formal camps, a minority can be confined by fear. When communities self-restrict movement, rely on volunteer night-guards, and avoid public visibility, they are being functionally contained. This is how pressure accumulates until exit becomes the only perceived option. Systematic policy is the sixth element. Ethnic cleansing does not require a written decree. In many cases, it proceeds through the combination of organised extremist violence and state failure: weak protection, delayed response, denial of communal targeting, and persistent impunity. Here, the core accountability question is state responsibility. Minority groups have accused the interim government of failing to protect Hindus, and the Yunus administration has denied those allegations. Denial, in the presence of repeated identity-targeted attacks, is not neutrality. It is an enabling posture. This is where the Yunus interim administration becomes central. The issue is not whether Yunus personally directs each assault. The issue is whether the state under his leadership has fulfilled its duty to prevent, protect, investigate, prosecute, and deter identity-based violence. When the outcome is repeated killings, recurring temple attacks, widespread property destruction, and the steady tightening of fear around a minority community, responsibility does not stop at the street-level perpetrator. It rises to the governing authority. The report also examines the role of Islamist forces operating in the current environment. Independent reporting notes that hardline Islamist actors have become more visible and influential since the fall of Hasina. This matters because ethnic cleansing campaigns typically require both ideological mobilisation and operational impunity: a narrative that dehumanises the target, and a system that fails to punish the perpetrators. Bangladesh is at a decision point. It can either reassert protection for all citizens and rebuild the rule of law, or drift toward a majoritarian model where minorities survive only as tolerated remnants. The world has seen this script before. The lesson from Rwanda and the Balkans is that early warning indicators are not “political noise.” They are the architecture of atrocity. What is required now is not performative condemnation. It is measurable action: robust protection for minority localities, transparent investigations, prosecutions that reach organisers and inciters, disruption of extremist mobilisation networks, and independent monitoring that makes denial impossible. Without these steps, the pattern described in our report will continue to harden. The Nobel label does not change the facts on the ground. The responsibility of the interim government is to stop the trajectory. If it cannot, it must be treated internationally as enabling an ethnic cleansing process by omission, denial, and impunity.